UPDATED 21Sep2018: Lilacs are one of my favourite shrubs, precisely because their blooms are so beautiful and so short lived. The lilac hedge I began establishing in the mid-1990s has also reminded me about the importance of long-term perseverance and details. All the photos here are of the hedge at my place.

UPDATED 21Sep2018: Lilacs are one of my favourite shrubs, precisely because their blooms are so beautiful and so short lived. The lilac hedge I began establishing in the mid-1990s has also reminded me about the importance of long-term perseverance and details. All the photos here are of the hedge at my place.

Where I live in Canada, the peak of lilac blooms usually happens during the first week of June. A week later, the blooms are beginning to fade. No one ever gets tired of lilacs in bloom because the colour and fragrance don’t last long enough to wear out their welcome. All this is why I planted a 300 yard long lilac hedge at my place over a period of three years beginning in 1995. That said, it’s only this summer that I solved a recurring problem I’ve been having all along.

Lilacs are hardy plants. They seem to grow like weeds, so I was surprised when particular sections of the hedge failed to thrive. Most of the hedge was fine, but a couple of sections totalling 75 yards had lilacs that grew slowly for a few years, then failed and died. Eventually, after years of struggling, all lilac bushes in these weak areas were dead, and the symptoms were always the same. Reasonable spring growth occurred, but then a weakening and yellowing of leaves as July rolled around. Despite lots of water during dry times of the year, these plants typically died over winter.

I replanted these troublesome sections twice, with mostly the same results over a period of years. Could there be nematodes in the soil sapping the life of these plants? No, tests came back negative. Could it be that the soil in these areas was just too heavy clay for lilacs to thrive? Probably not, since the thriving sections of my hedge were in the same kind of soil. Now, 20+ years later, I believe I’ve solved the mystery of the failing lilacs. The problem turned out to be something I never imagined. A couple of things, actually.

Over the years I’d applied a weak solution of water soluble fertilizer to my lilacs as I irrigated them, and I figured this was enough to bring nutrient levels up if there had been any deficiencies. But having exhausted all my options for dealing with these weak and dying lilacs, I did a soil nutrient test. I should have done this earlier because nutrients were low, though not much different between the healthy and poor sections of hedge.

Potassium registered especially low in the soil tests, and phosphorus wasn’t anything to brag about, either. That’s why I started applying 6-24-24 granular fertilizer by hand in spring, and another in the fall. The difference was noticeable, but the die-back continued. Good growth in spring was always followed by weakening and yellowing over the summer. Weak bushes would begin dropping leaves in early September while most other sections in my lilac hedge grew big and green and vibrantly.

“You might have a micronutrient deficiency”, explained my friend Birgit. She’s an agronomist and though she’s never consulted on a crop of lilacs, I decided to look into her suggestion. Micronutrients are elements that need to be present in tiny quantities for some plants to thrive. Certain plants are more susceptible to micronutrients deficiencies so I did some research. Online I found examples of yellow leaves on lilacs and failure to thrive when manganese is low. This was a new idea to me and it looked like a winner. I did another test, this time including micronutrient analysis. Sure enough, manganese was definitely on the low side.

Next spring, Birgit supplied me with some granular manganese fertilizer and a liquid I could spray onto the leaves after diluting with water. Do you ever feel a high level of enthusiasm when you think you’ve found the cause of a recurring problem? I sure do, and that’s how I felt when the lilacs seemed to be more vigorous after the manganese treatment. Seemed to be, but the vigour didn’t last. Come September of 2017, the weak lilacs were looking weak again. Not as weak as usual, but still not thriving everywhere. Some were dying.

It’s sometimes difficult to decide when to stop trying to solve a problem, but I knew I wasn’t ready to give up yet. Birgit suggested another soil sample for micronutrient testing, but this test would be different. One sample was from a thriving part of the hedge and another from the failing part. The crazy thing is, results of the two samples looked pretty much the same. Manganese was much higher now than it was the last time (because of the granular and foliar manganese I’d added), but the two samples were disappointingly similar. The poor areas of lilac actually had a couple of better nutrient levels than the thriving parts of the hedge. One thing was different, however, one small thing.

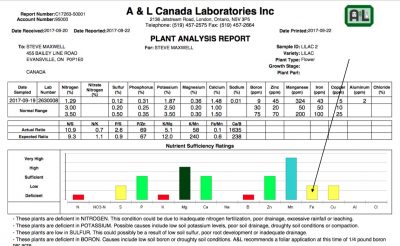

Iron was a little lower in the poor section than the thriving areas. Not much, but it did show up as a yellow alert on the soil test results graph. That’s what you can see here. But then again, so did other elements. Just the same, iron was really the only straw I had to grasp since it was the only small difference between the thriving lilacs and dying ones. Birgit recommended a lawn fertilizer with extra iron, normally meant for making grass greener. I wasn’t interested in greening things, the fertilizer was just a handy source of iron. Would it be enough? I just wanted lilacs that grew like they were supposed to. I spread, waited and watched my lilacs this past growing season.

Iron was a little lower in the poor section than the thriving areas. Not much, but it did show up as a yellow alert on the soil test results graph. That’s what you can see here. But then again, so did other elements. Just the same, iron was really the only straw I had to grasp since it was the only small difference between the thriving lilacs and dying ones. Birgit recommended a lawn fertilizer with extra iron, normally meant for making grass greener. I wasn’t interested in greening things, the fertilizer was just a handy source of iron. Would it be enough? I just wanted lilacs that grew like they were supposed to. I spread, waited and watched my lilacs this past growing season.

This summer has been desperately dry where I live on Manitoulin Island, but despite this my sickly lilacs seem to have turned the corner. They look better this September than they ever have before. Much better. They’re still small and stunted after years of decline – some barely clinging to life – but they show a promise I haven’t seen before. They really do. I think I’ve got the mystery solved, and it has reminded me of something vital.

Sometimes very little things in life can make big differences – all the difference, in fact. And sometimes extreme perseverance is the only way to bumble our way through life’s challenges, bumbling because we can’t see the real causes of problems. If only we could see more clearly, identify problems for what they really are, then tackle them head on. Wouldn’t it be so much easier to live if we didn’t have to deal with partial ignorance?