Ever wonder what it’s like to move from the city to a vacant rural property deep in the country? You can read about it all right here. This is the first chapter in my book about the experiences of my wife and I and our family as modern homesteaders on Manitoulin Island, Canada beginning in the mid-1980s. Woven throughout the story you’ll meet some of the people who’ve been part of the adventure so far. You’ll also experience something of what it’s like on Manitoulin Island, along with stories about tools, land, projects, gardening, farming, machines, metal, stone, good work, plus practical matters probably only interesting to people who are unusual like me . . . I hope you’re one of us people and that you find something here to enjoy.

Ever wonder what it’s like to move from the city to a vacant rural property deep in the country? You can read about it all right here. This is the first chapter in my book about the experiences of my wife and I and our family as modern homesteaders on Manitoulin Island, Canada beginning in the mid-1980s. Woven throughout the story you’ll meet some of the people who’ve been part of the adventure so far. You’ll also experience something of what it’s like on Manitoulin Island, along with stories about tools, land, projects, gardening, farming, machines, metal, stone, good work, plus practical matters probably only interesting to people who are unusual like me . . . I hope you’re one of us people and that you find something here to enjoy.

*************

CHAPTER ONE: SURPRISED BY REALITY

Aspirations can be strange things. That’s because when you begin to experience the reality of what you’ve been dreaming of, it’s often quite different from what you imagined. And this difference – the difference between theory and practice – can be discouraging and scary if you don’t expect it. The biggest “theory-meets-practice” event of my life so far happened on May 15, 1986. That was the day I woke up in a tent on Manitoulin Island, alone and 350 miles from my boyhood home. I was a homesick 22 year old with a few hundred dollars in the bank. I also happened to be completely drowning in regret of the worst sort – the regret that used to be enthusiasm. You know those beautiful angels that morphed into specters of death at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark? I felt like the Nazi guy with the round glasses and melting face. All I could think of as I woke up in my tent on that bright morning in May was that I’d made a massive mistake. I’d blown all my money on a foolish dream and a useless piece of land in the middle of nowhere. I’d bitten off something way too big to chew, and I’d wasted a whole lot of time figuring that out.

For the previous four years I’d dreamed of owning rural land of my own. It would be a quiet, beautiful place where I’d build my own house, fill it with furniture I made, grow food, raise animals, raise kids with my wife-to-be Mary, and heat with firewood. I’d be happy and free from the rat race. This was the dream that fueled me for years previously. But somehow, in the space of a couple of days, it had all turned to deep regret.

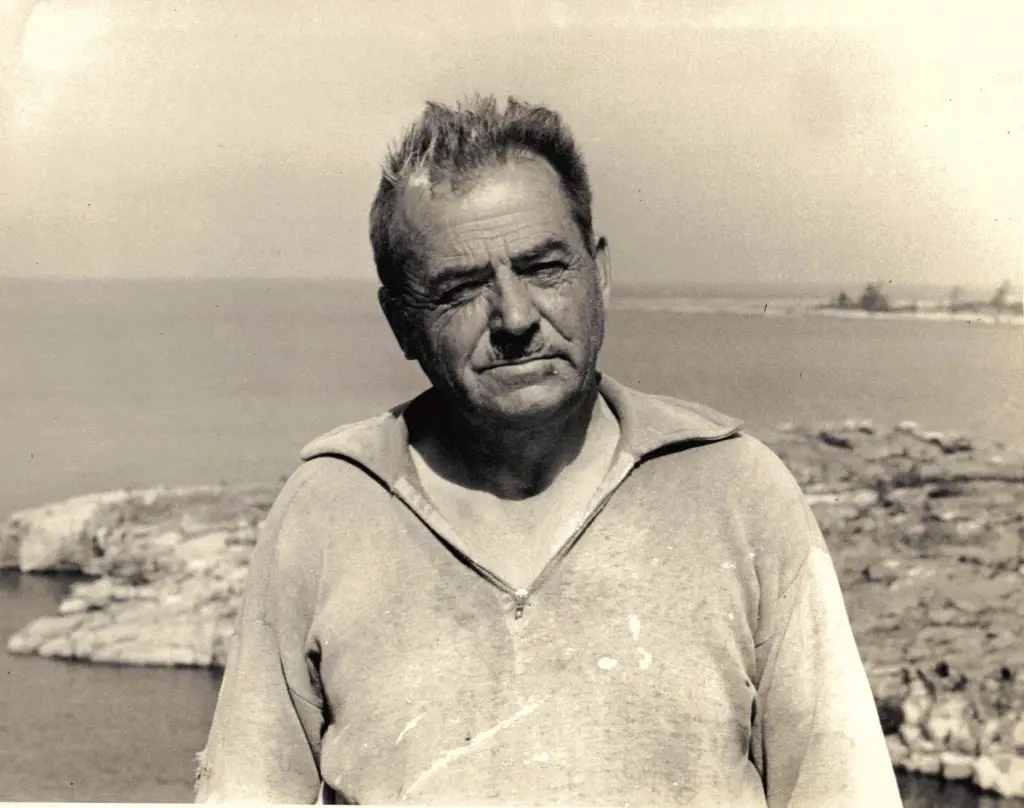

I’d grown up in the suburbs of Toronto, Canada in the 1960s and 70s, and though I’m thankful for the comfortable and safe life my parents gave me, I never was a city guy. The lack of natural beauty always left me empty. I’m sure my attraction to the country and addiction to beauty had something to do with fond memories I’d gained at the family cottage on the shores of Georgian Bay. It was a log place built in 1923 by a bachelor great uncle of mine named Ken Evans. That’s him below.

Uncle Ken came back from WWI looking for a quiet place to live, and he found it on 4 acres along the water in a spot called Pointe-au-Baril, Ontario, Canada. Like many men of that time, he’d been swept up in the glorious fantasy of war. He joined the Canadian forces, but when he discovered that his unit would only have ceremonial duties in Canada, he went AWOL, got on a ship headed for England and joined the British forces to see some real fighting. He certainly did, too. He survived Paschendale, Ypres and the Dardanelles. He came back to Canada completely opposed to killing of any kind. He never ate meat again and wouldn’t even kill mosquitos. Uncle Ken died 8 years before I was born in 1963, but somehow his cabin dream settled in my soul anyway.

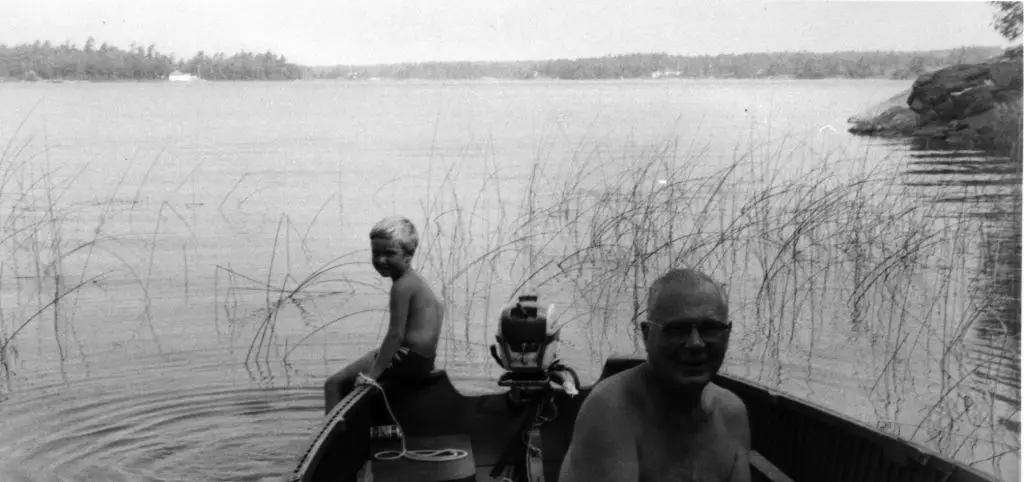

For a beauty-starved boy from suburbia, the cottage was magic of a most powerful kind. Fishing whenever I wanted; unsupervised use of a Red Ryder BB gun that was my dad’s when he was a boy; a woodshed full of Uncle Ken’s tools; and nothing to think about all summer long except bacon and eggs in the morning, swimming and fishing all day, with frequent roast beef dinners at night. The cottage was my magic land and my grandfather, Ken Maxwell, was the magician. He was mostly retired by the time my cottage years began, so we’d go to the cottage together for weeks on end. My grandmother died in 1967 when I was 4 years old, so Grandpa became an accomplished bachelor.

Grandpa cooked for us both, kept the woodstove going when it got cold, and taught me to plane boards, cut firewood patiently with a Swede saw, drive a motorboat and play crokinole on the kitchen table at night. As we flicked the little wooden disks across the crokinole board with the sound of crickets wafting in through open windows, we listened to Grandpa’s tube radio. It was AM only, ancient even at that time, and it took a few minutes to warm up after you turned it ON by clicking the wooden volume knob. Somehow, mysteriously to me as a boy, that old radio brought in stations from thousands of miles away at night. Only at night, though. During the day we got a few faint stations from other places in Ontario, only because there wasn’t anything local. But when summer nights came, it brought southern accents into the cottage kitchen, voices with friendly lilts from radio stations in Tennessee, Louisianna, New York, Florida, Kentucky and other far-flung places. The voices would wax and wane on their own as they came out of the radio. Sometimes there was music, other times radio dramas. I know now this sort of thing is called “skip transmission”, but at the time it was just part of the mystique of life outside the city for me.

Can you see how a few years of this cottage stuff was enough to ruin me for anything other than some kind of country life? The whole thing came to a head in 1976, the summer I was 13 years old. I’d taken on summer work by then to earn some money, and this took away most of my cottage time with Grandpa. One afternoon when I was covered in the nasty smelling, light green oil-based paint I was using to coat a garage for a neighbour, I felt like little Jackie Paper leaving Puff the Magic Dragon. I was growing up and I wasn’t at the cottage. That’s when a thought occurred to me. Surely there’s some way I can earn money and enjoy the cottage at the same time, right? This was the first time I remember thoughts that would eventually lead me permanently to the country and the deeply satisfying work and life I have here. It’s like that good old song about Puff, but with a happy ending.

Can you see how a few years of this cottage stuff was enough to ruin me for anything other than some kind of country life? The whole thing came to a head in 1976, the summer I was 13 years old. I’d taken on summer work by then to earn some money, and this took away most of my cottage time with Grandpa. One afternoon when I was covered in the nasty smelling, light green oil-based paint I was using to coat a garage for a neighbour, I felt like little Jackie Paper leaving Puff the Magic Dragon. I was growing up and I wasn’t at the cottage. That’s when a thought occurred to me. Surely there’s some way I can earn money and enjoy the cottage at the same time, right? This was the first time I remember thoughts that would eventually lead me permanently to the country and the deeply satisfying work and life I have here. It’s like that good old song about Puff, but with a happy ending.

Another thing that led me to the country was a flash of insight I had one evening while driving on a tractor with my high school friend Paul. We’d just finished a day’s work loading square bales of straw into a barn just outside the zone of suburbia that my house was in. I was 18 then, earning money in the summer before my last year of high school.

“What’s involved in buying a piece of farmland,” I asked Paul, the idea having just flashed into my mind. Paul was much more experienced with farm and rural life than I was. “What are taxes likely to be? How much can you earn farming?” These weren’t typical questions to be asked by a young man who’s dad wore a suit every day and carried a briefcase to work, but I asked them anyway.

What was my motivation? I didn’t know fully at the time, but I do now. As 19th century philosopher Henry David Thoreau said, I wanted “to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

What would I do for a living in the country? I wasn’t sure. How would I learn all the practical skills required? I didn’t know, but “how hard could it be”, I thought? One thing I did know for sure: I’d do whatever it took to make my work follow my choice of where to live, not the other way around.

This rural dream of mine was to be a do-it-yourself venture, partly because DIY has always appealed to me, and partly because I couldn’t afford anything else. A shoestring budget was a necessary part of the equation. But where, exactly, can a person begin to build a shoestring modern homestead life? Finding a place to do this was harder than I expected.

After that fateful evening on the tractor with Paul, I spent four years casually touring the southern part of the Canadian province of Ontario where I lived, always with an aim to finding “the place”. It’s surprising how much disappointment this can yield when ideals meet reality and “the place” never even comes close to showing up.

Many regions of southern Ontario are all about very serious farming, but that usually means brown rivers silted up like chocolate milk, with too much corn and way too few trees. On the other hand, areas that had lots of trees and clean lakes usually have no soil nor agricultural potential. There isn’t a hay baler within miles of these places. Most everything I found was too expensive anyway. So much of life eventually comes back to money, doesn’t it?

By my early 20s I’d accumulated about $13,000, mostly from summer jobs I’d had ever since I started cutting grass professionally when I was 12. I was a saver. A building contractor named Andy Steier hired me back then to use his John Deere lawn tractor to cut the five acres of grass he had around his country estate the summer I turned 12. The job took me 8 hours if I worked fast, for which Mr. Steier paid me $30. He didn’t care if the job took me one hour or one month. Payment was for a good job done. No hourly stuff for Mr. Steier. One autumn, in payment for raking all the leaves from his yard, he gave me a single-shot, Winchester.410 shotgun. You could buy a gun like this without paperwork in any Canadian hardware store for $40 back then, and a boy could keep a gun like this under his bed if he was quiet about it.

I never earned big money growing up, but I come from a long line of frugal people, so I never spent much. But just the same, saving can only get you so far. A wise and successful businessman I know once told me he’d much rather have good luck than good management. I agree. In 1980, I had the good luck of buying government of Canada savings bonds that happened to pay a whopping 20% per year interest. I didn’t realize what a windfall this would be. It was my mother’s idea. As the world went crazy with high interest rates, my little stash of grass cutting money pretty much doubled automatically while I was finishing high school and university. In the end, when those bonds matured 4 or 5 years later, they made all the difference to my homestead dream. I still only had a few pennies as far as land went, but I was just barely in the ballpark for buying a little chunk of cheap heaven. The trick was to find it.

With nothing to be found in southern Ontario after four years of day trips with my girl friend (now wife), Mary, we venture north to what they call the “little clay belt” near New Liskeard in northern Ontario. Mary was born in British Guyana, in South America, and her father’s work brought her to Canada in 1981. We met in grade 13 and we’ve been together ever since. The prospect of living a rural life was completely foreign to her, but she was willing to give it a try.

Most of northern Ontario had its layer of soil scraped off by glaciers a long time ago, but the little clay belt was different. For reasons no one can be completely sure about, this small area has deep, rich soil. It’s also surrounded by and punctuated with lakes, rivers and some pretty good trout fishing. That sounded like an unusual combination worth checking out, so we did.

Seven hours drive north of my parents’ home where I was living in suburban Toronto, Mary and I crossed into quite a distinctive zone on our journey. For hours we’d seen nothing but granite rocks, pine trees and scarce soil. All of a sudden there was real farmland in the little clay belt. It was quite a stark change, but not what I expected. Even in August, the place seemed like winters would be cold. The trees were stunted compared with what I was used to, and there was a complete absence of apple trees. The little clay belt wasn’t doing it for us. Not even close. More disappointed.

By now I was losing hope that I’d ever find a region I’d be happy to invest my life into. Traveling south, going back home, we decided to take a detour to a place I’d heard of but knew nothing about. It was called Manitoulin Island and it’s connected to southern Ontario by a 1 3/4 hour ride on a car ferry that docks on the south-east corner of the island, in a village called South Baymouth. Approaching the island from the north, as we did, there’s a single lane swing bridge that allows car and truck traffic on and off the northeast corner of Manitoulin at a town called Little Current. This swing bridge was built in 1913 for trains only, then converted to handle both road and rail traffic in 1946 when the first roads off the island opened up. In the 1980s rail was abandon altogether, so the bridge has been road-only ever since.

Within 5 minutes of crossing the swing bridge, we both knew that somewhere on this island was the land for us. The place felt very right, but as I would soon discover, there were facts in favour of the place too, not just feelings. Manitoulin has all the qualities of a southern Ontario hardwood landscape with farmland, but also clean lakes, small villages and a geographical diversity I’d never seen before. That’s because farming can’t happen everywhere on Manitoulin. It’s limited by geography. More than half the island has soil that’s way too shallow for agriculture. This makes for small fields where deep soil does exist, with lots of forest between areas growing hay, a little grain and pasture. In some ways, visiting Manitoulin is like stepping back in time. That’s true even now. The swing bridge below is one of two ways to get to Manitoulin, The other way is that car ferry and the 1 3/4-hour crossing time I mentioned.

Within 5 minutes of crossing the swing bridge, we both knew that somewhere on this island was the land for us. The place felt very right, but as I would soon discover, there were facts in favour of the place too, not just feelings. Manitoulin has all the qualities of a southern Ontario hardwood landscape with farmland, but also clean lakes, small villages and a geographical diversity I’d never seen before. That’s because farming can’t happen everywhere on Manitoulin. It’s limited by geography. More than half the island has soil that’s way too shallow for agriculture. This makes for small fields where deep soil does exist, with lots of forest between areas growing hay, a little grain and pasture. In some ways, visiting Manitoulin is like stepping back in time. That’s true even now. The swing bridge below is one of two ways to get to Manitoulin, The other way is that car ferry and the 1 3/4-hour crossing time I mentioned.

Quite unexpectedly, Manitoulin also had something of an east coast, maritime feeling. That was a pleasant surprise. The waters of Lake Huron and the North Channel are big enough that they give the coastal towns of Manitoulin the feeling of being by the sea. The impression was enhanced by the fact that you could buy local fish caught just offshore. The largest fishing venture is owned by a family named Purvis that has been in the business since the 1880s. Smoked chub was common during that first visit in 1985. These days it’s Lake Trout and Whitefish.

Mary liked Manitoulin, too. She felt the magic, so we visited some real estate agents, such as they were at the time. In many ways, Manitoulin really is the island time forgot, and this was especially true in the 1980s. The only radio station then was the government-run Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. At the time it was the radio equivalent of a pair of sensible orthopaedic shoes. Every country telephone service in each house was on a party line where you shared a single phone connection with 3 or 4 other households. There were no other options. You could hear the phone ring for other people in your own home, and the nosier folks would have no shame listening in on calls. Real estate agents were a new idea on Manitoulin in the 1980s, too. A few freelance agents had set up small businesses in their homes or in old rented spaces. There were no brand name agencies, just mom and pop operations running under their own last names.

Mary and I soon learned that most 100 acre farms with no house or barn were going for $30,000 at the time. That was much cheaper than I’d seen anywhere else in Ontario, but still way more than I had to spend. Knowing what I do now, I should have borrowed money and bought ten of those $30,000 farms. Thirty years later they’re all selling for more than 5x this amount.

One particular 91.5 acre piece of land caught my eye. “Half farmland, half forest”, said the type-written note taped to the inside of the window of an otherwise-empty shop on the main street of Gore Bay. The $18,000 asking price was attractive enough that I called the phone number. A woman with a thick German accent answered. Her name was Kitty Grigull, she was a kind of informal real estate agent, and she’d take Mary and I out to see the property whenever we wanted.

This land was deep in the country – deep even by Manitoulin standards – and Mary and I soon found ourselves walking behind a most vigorous 76 year old man. His name was Ivan Bailey, he was born in 1909 and he grew up on the property we were interested in before he sold it to the current owners in 1973. Kitty took us to see Ivan, but Ivan was the man who knew the property. He’d been there his whole life and he sure knew how to walk quickly through fields and forests.

Ivan Bailey was the kind of old timer who was lean and muscular from a life spent in hard work. Many years after I met him, when I carried Ivan out of his house into a waiting car after he had a heart attack, I could still feel plenty of muscles in his arms and shoulders as I cradled him like a baby into the back seat, his bald head just below my chin. Ivan was tough, too. He survived that heart attack and lived another 5 years before cancer finally got him.

The day was a little rainy, so Ivan loaned us each a pair of rubber boots as Mary and I scrambled to keep up with this ancient backwoods guide. The land looked good, and Ivan said it could grow anything. He was the kind of old guy you automatically believe. Ivan showed us the fields, one of which had just grown a crop of grain. He showed us “the spring”, a crack in the limestone bedrock that always had water within 6 feet of the surface. He also showed us the forest, including some pretty good sized white cedar trees in the back of the property. “There are enough good ones there to build a log cabin”, he explained. To be honest, this land seemed good to me, but not great. I wasn’t immediately convinced, but Mary felt differently. “This is the place, Steve. This is the place for us.” She was right.

Within two days of Ivan’s rubber boot tour, I called my parents from the road on a pay phone asking them to loan me what I needed to increase my $13,000 stash into $16,500 – the price I’d settled on with the owners through Kitty. They agreed, and within a month the deal was sealed. It was a happy time indeed, but like all happy events, the joy didn’t last forever. I didn’t know it then, but success is always about continuing towards the dream even when you don’t feel like it. Success doesn’t always feel like success when you’re in the middle of succeeding.

Want to be a key part of making The Bailey Line Road Chronicles a complete published book? I’m looking for some good patrons to partner with me to complete this project. Just a couple of dollars a month gets you your own copy of the story when it’s done, and your name on “The Patrons” page. Click here to find out more.

Want to be a key part of making The Bailey Line Road Chronicles a complete published book? I’m looking for some good patrons to partner with me to complete this project. Just a couple of dollars a month gets you your own copy of the story when it’s done, and your name on “The Patrons” page. Click here to find out more.

Click here to read The Bailey Line Road Chronicles: Chapter Two – The Wake Up Call